Both India and the US are headed for big elections next year in April-May and November respectively. How their economies perform this year and closer to the polls — in terms of growth, jobs generated, inflation and real incomes — would matter for Narendra Modi and Joe Biden.

From this standpoint, official economic data released this month for the two countries contain reasons for concern.

US inflation, unemployment

Start with the consumer inflation numbers for the US, based on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index prepared by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

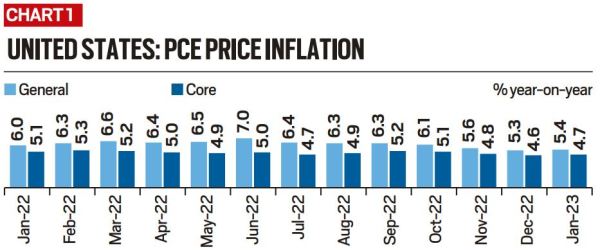

The overall PCE price index for January was 5.4% higher than its level in the same month of 2022. Core PCE inflation, which excludes changes in consumer energy and food prices that tend to be more volatile, stood at 4.7% year-on-year.

Both ‘general’ and ‘core’ inflation have been ruling well above the US Federal Reserve’s target of 2%. While the former has fallen from its June high of 7%, the latter, considered a more accurate gauge of the underlying inflationary trend in the economy, has been stubbornly stuck at around 5% (Chart 1).

Chart 1: PCE price inflation in US

Chart 1: PCE price inflation in US

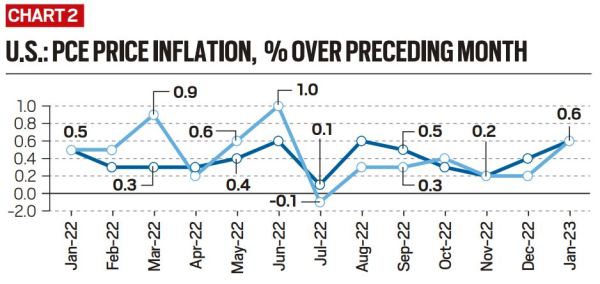

But more than year-on-year (Jan 2023 over Jan 2022), it’s the month-on-month (Jan 2023 over Dec 2022) inflation that has been the shocker from the PCE price index data issued on February 24. The increase in prices over the prior month was 0.6%, translating into an annualized rate of 7.2%. Chart 2 shows this monthly rise was the highest since May for the general and August for the core index.

Chart 2 shows this monthly rise was the highest since May for the general and August for the core index.

Chart 2 shows this monthly rise was the highest since May for the general and August for the core index.

The above data should be seen along with an earlier employment situation report of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, released on February 3. It showed the total non-farm payroll employment surging by 517,000 in January against an average monthly gain of 401,000 in 2022 — the most since the 568,000 in July.

Advertisement

Moreover, the unemployment rate, at 3.4% in January, fell to its lowest since May 1969.

Monetary policy implications

The January inflation and employment data point to two things.

First, inflation has returned after seemingly retreating towards end-2022, although even those numbers were way elevated vis-à-vis the US central bank’s goal of keeping the annual PCE price index increase to 2%.

Advertisement

Second, falling unemployment, which reflects demand for labour outstripping supply, has complicated the Fed’s job. The labour market’s tightening — going “out of balance”, according to Fed officials — is putting upward pressure on wages and, in turn, driving up inflation.

How does the Fed respond? Given its commitment to price stability and getting inflation back down to 2%, it has no choice but to raise interest rates further. As credit becomes more expensive, businesses and consumers will hire and spend less. Economic activity slowing would then reduce overall demand, help cool overheated labour markets, and eventually bring inflation under control.

It is important, however, to note that the Fed has already substantially hiked its funds rate — from a target range of 0-0.25% till March 16, 2022 to 4.5-4.75% in the last Federal Open Market Committee meeting on January 31-February 1.

Hiking further would risk what economists term a “hard landing”. When inflation is persistent at 5% and the target is 2%, interest rates will have to be increased high and fast enough, and kept at those levels until economic activity moderates sufficiently.

That would mean a sharp downturn or recession just ahead of the US presidential elections. It is the opposite of subdued growth or a mild recession (“soft landing”), which follows the Fed having to raise rates only slowly and in small amounts to reduce inflation from, say, 3% and cool an economy not that overheated.

Advertisement

An indicator of where interest rates are headed is provided by yields on 10-year US government bonds. Between February 2 (before the jobs report) and February 24, these — basically what the government would pay for a 10-year loan — have soared from 3.40% to 3.95%. Clearly, the markets are pricing in significant monetary tightening by the Fed in the coming days.

Layoffs and resignations

How does all this square up with the mass layoffs by the likes of Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Meta, Tesla, Salesforce, IBM, Ericsson, Zoom, and SAP?

Advertisement

One reason may have to do with jobs cuts happening more among skilled and better-paid employees, especially in tech companies that probably over-hired earlier.

A second factor could be the US labour force shrinking relative to its working population (aged 16 years and above). That ratio — called the labour force participation rate — has fallen from 63.1% in 2019 to 62.2% in 2022. In other words, almost 1% of working-age Americans, who were employed or looking for jobs pre-pandemic, have exited the labour force.

Advertisement

A third, more interesting, explanation is from Yongseok Shin, an economics professor at Washington University in St Louis. In a recent National Bureau of Economic Research paper, he has estimated [https://ift.tt/M6J8WTi] an average decline of 11 hours worked per person per year in the US between 2019 and 2022. The labour market is tightening not just because fewer Americans are working; even those working are choosing to work fewer hours.

One of the pandemic’s more permanent legacies has been the “Great Resignations” and “Quiet Quitting”. In Shin’s description, these are people opting to “recalibrate their work-life balance in the direction of fewer work hours”. The various cash transfers and economic reliefs extended during the pandemic would also have enabled such reassessment of life priorities.

The situation in India

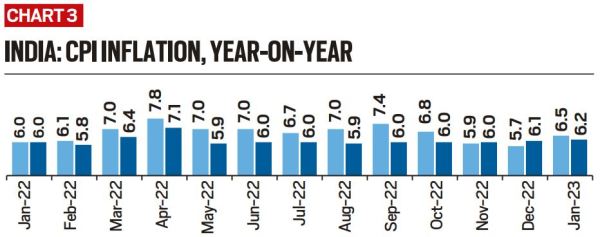

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is facing a similar dilemma, with the declining trend in the consumer price index (CPI) inflation reversing in January. The central bank’s mandate requires it to keep annual CPI inflation to 4%. While this target is subject to an “upward tolerance limit” of 6% — making it less rigid than the US Fed’s 2% — even these levels were breached for both general and core inflation in the latest reported month (Chart 3).

Chart 3: CPI inflation in India

Chart 3: CPI inflation in India

The greatest source of uncertainty for the RBI now is the impact of higher-than-normal temperatures on wheat and other rabi crops, due for harvesting from March-end. If temperatures spike further, as they did last March, it could reignite inflation in food. Also, a pick-up in rural wages appears underway, with the average year-on-year increase in rates exceeding CPI inflation since November.

Like the Fed, the RBI, too, has hiked its benchmark repo lending rate from 4% to 6.5% since early May 2022.

How much more it may hike to dampen demand — and risk a “hard landing” — would possibly be as much a function of electoral compulsions as of economics.

"soft" - Google News

February 27, 2023 at 07:40AM

https://ift.tt/TMsXC2a

‘Hard’ vs ‘Soft’ landing: Policy choice before central banks in both US and India - The Indian Express

"soft" - Google News

https://ift.tt/ECKNoM5

https://ift.tt/8Db9Xi0

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "‘Hard’ vs ‘Soft’ landing: Policy choice before central banks in both US and India - The Indian Express"

Post a Comment